Myanmar’s forests have provided livelihoods and wealth for many years but are now under enormous strain. The Myanmar Selection System—a scientific system of sustainable harvesting and management—was one of the earliest management systems, originating in the 19th century. However, since at least the 1970s, conflict, land concessions, and illegal and unsustainable harvesting of timber for export, especially the highly sought-after Myanmar Teak, have degraded forests. While successive governments have taken steps to acknowledge and address some of these issues, plans for expanding plantation agriculture, hydropower, and mining conflict with those steps.

The harvesting of timber for export has degraded forest land in Myanmar. Photo by James Anderson, World Resources Institute via Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Ecology and Uses

Forests in Myanmar are primarily mixed deciduous, temperate evergreen and tropical evergreen.1 They are rich in biodiversity, containing a recorded 11,824 species, 8 of which are endemic to Myanmar.2 There remains important forest complexes and biodiversity corridors in the South, West, and North. These forests host a number of endangered species such as the Indochinese tiger, Asian elephant, and Malayan tapir.3

Economy

The Republic of Myanmar estimated that forestry contributed 245 billion MKK (130 million USD) to Myanmar’s economy in 2015-16, or roughly 0.2% of GDP.4 Official figures placed forest exports at 207 million USD that same year, the last year with data. However, illegal timber exports are estimated to be worth four times the value of legal exports.5 Moreover, earnings after the 2014 export ban on raw timber were depressed in 2015-16, the year from which these figures are drawn.

Also, the above figures measure just direct sales of timber and forest products. Forests also play crucial roles in filtering water, preventing erosion, and storing and releasing nutrients, referred to as ecosystem services. One estimate of the value of the ecosystem services provided by forests in Myanmar placed it at 7.08 trillion MKK (about 7.29 billion USD).6 Forestry also provides 4.1% of total employment in Myanmar.7

As many as 70% of people living in rural Myanmar are highly forest dependent,8 with higher levels among the poor. Rural communities depend on forests for wood fuel, bamboo and rattan, fodder and forage for livestock, wild fruits and meat, and medicine.9 Many practice shifting cultivation with long fallows while preserving stands of old growth forest.10

Forest Cover Changes

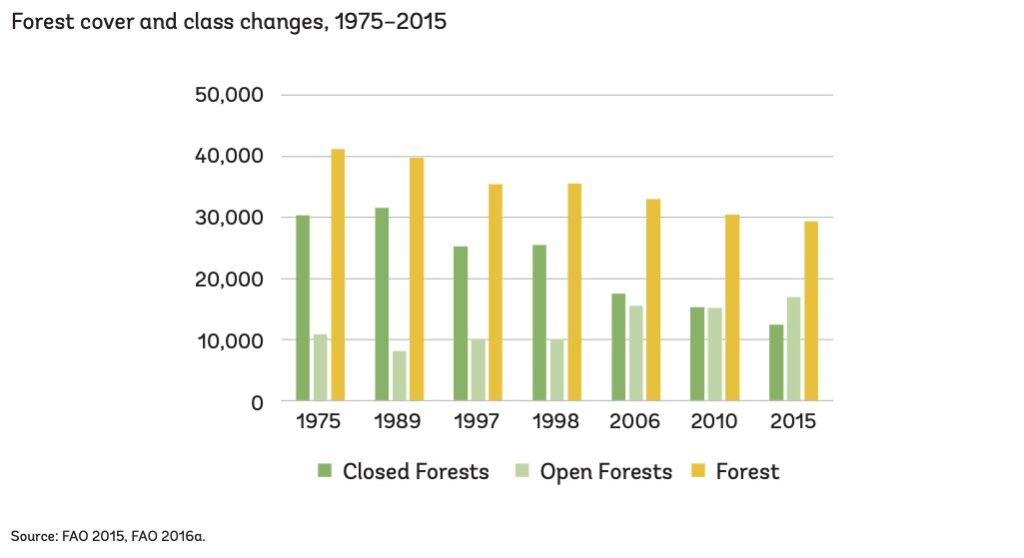

The FAO-verified officially reported forest cover in Myanmar was 43% of land area in 2015. This marked a decline of 26% from 1990, representing one of the largest declines in the world.11 Of note, the 43% figure was not actually measured in 2015, but calculated based on 2010 data and an assumed trend of forest change.12

Graph by FAO from The World Bank, 2019. Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis. Terms and conditions for reuse available here.

The above report defines “forest” as “[l]and spanning more than 0.5 hectares with trees higher than 5 meters and a canopy cover of more than 10 percent or trees able to reach these thresholds in situ.”13 This is a “land-cover” definition, since it depends on actually detecting forest rather than just the designation of a piece of land as forest land. The government of Myanmar also includes in its definition of forest “temporarily de-stocked land for which the long-term use remains forest”, or forest land that has been cleared but subsequently replanted with trees or is intended to be replanted. It also excludes agricultural or urban land even if it meets the 10% tree cover threshold. Though not mentioned in the above report to the FAO,14 the Myanmar government subsequently claimed to the United Nations REDD+ Programme to have applied these criteria in its FAO assessment.15

The decline of 26% in forest cover, as noted above, is what the government of Myanmar, in keeping with the FAO’s definition, refers to as “deforestation”—the conversion of forest land permanently to non-forest land.16 Myanmar’s forests have also experienced degradation, reforestation and afforestation. These categories do not easily add and subtract to determine total forest cover change.

Definitions

Degradation is when land remains officially classified as forest but tree cover, biodiversity, and/or ability to provide ecosystem services decline; Reforestation is when land that was until recently forest is replanted or naturally regenerates. Afforestation is when land that was not recently forest becomes forest either through natural expansion or planting.

Drivers of Forest Cover Change

The above categories of change are a helpful starting point for identifying the drivers of forest cover change.

Deforestation

Both official reports and independent assessments have identified conversion of land for agriculture as a major driver of deforestation. Myanmar’s report on drivers of deforestation to the UN-REDD Programme identified agriculture as the major driver, responsible for about 1 million hectares of deforestation between 2002 and 2014.17 For better understanding, it is common to distinguish between large scale plantation agriculture and small scale and/or shifting cultivation.E.g. 18 This report noted that it is primarily plantations replacing forests. This finding, seen beside an increase in the area allocated for agribusiness of 170% between 2010 and 2013 alone,19 suggests that plantation agriculture is primarily responsible for deforestation. On the other hand, different studies also identify shifting cultivation as a significant driver.

Former natural forest has been converted into teak plantations in Myanmar. Photo by James Anderson, World Resources Institute via Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Infrastructure development is also considered a major direct and indirect driver of deforestation. In the early 2000s, mapping showed that deforestation was concentrated around road development, suggesting a correlation.20 Currently, the development of energy and natural resource infrastructure is often associated with deforestation. For example, hydropower reservoirs are currently estimated to cover about 139k hectares of land, mostly former forest, with a further 232k hectares to be covered by planned projects.21

Forest fires have also been a source of tree cover loss, but it is unclear whether this type of forest loss is represented in official statistics22

Degradation

Timber harvesting, both legal and illegal, is likely a large driver of degradation.23 For instance, although the Forest Department has calculated a scientifically derived annual allowable cut (AAC), in recent decades legal teak production quotas have exceeded the AAC by at least 15%.24 Furthermore, domestic demand for both timber and fuel is commonly met through illegal harvests.25 Lucrative export markets abroad are the destination for huge quantities of illegal timber.26 Researchers warn of an irreversible decline in forest diversity and of timber quality resulting from the present rates of extraction.27

Degraded forest land in Myanmar. Photo by James Anderson, World Resources Institute via Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Afforestation/Reforestation

In 2010, Myanmar reported that roughly 27,400 hectares of land were reforested, referring to trees naturally regenerating or replanted by humans on land already classified as forest use. All of it was categorized as replanted by humans, or “artificial reforestation.” The report also noted that reforestation numbers might also include afforestation, defined as forest cover being established on land previously not classified as forest use, because differentiation between the two activities was not possible.28 In 2016, the Forest Department produced a 10-year plan envisioning a modest increase in reforestation to at least 32,500 hectares a year.29 Reforestation is especially envisioned for areas under Community Forestry (see Forest Policy and Administration).

Wood Products Trade and FLEGT

Teak logs awaiting inspection at a factory yard in Myanmar. Photo by EU FLEGT Facility via Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Four key elements can help to understand the context of the timber trade in Myanmar: the role of the Myanmar Timber Enterprise, Myanmar’s role as a raw timber exporter, the presence of both unsustainable and illegal timber harvesting, and limited data.

State Monopoly

A state-owned agency under the Ministry of Forestry, the Myanmar Timber Enterprise (MTE), has had the sole right to harvest timber from Natural Forest in the Permanent Forest Estate since 1993. Although for many years, MTE sub-contracted out harvesting to private enterprises, these concessions were banned in 201630 to cut down on corruption and illegal harvesting.31 In 2018 there were also reports that the government planned to transform MTE into a state corporation under private management.32 The status of this transition remains unclear.

Some private timber companies have been allowed to cultivate plantations since 2006, some of them in former reserved forest land.33

Limited Value Adding Capacity

Myanmar has historically exported primarily raw timber—logs rather than sawed and treated lumber. Because this limited the returns that Myanmar could earn on its timber resources34 and the risk for investing in wood-processing was high,35 n 2014, the U Thein Son government banned all exports of raw timber to give the domestic wood-processing industry time to develop.36 However, in June 2019, the NLD decided to re-allow exports of raw timber, including teak, from both public and private plantations.37 While the ban on raw timber exports from natural forests and monitoring systems remain in place, it may be difficult to prevent timber harvested illegally from natural forests from mixing with plantation timber. This may undermine the goal of the initial ban to build up the domestic processing sector. It also risks reducing revenue earned from taxes on legal exports, and could undermine Myanmar’s nascent Timber Legality Assurance System (see below).

Extensive Illegal and/or Unsustainable Harvesting

As mentioned, legal harvesting in state-run forests has for many years exceeded the AAC. Moreover, illegal logging has accelerated in the past 40 years. Estimates of timber from Myanmar on international markets that is illegal ranges from 47.7%38 to 75%.39 Border areas which also are the site of much separatist activity are considered likely to be primary sources of illegal timber.40 Forest lands granted as agricultural concessions are another main source of timber, perhaps the dominant source for non-teak woods. This so-called “conversion timber” is considered legal if harvested with a permit. It is not separately counted in official statistics. Instead, it is mixed with other sources of timber in Yangon and stamped as MTE wood, posing difficulties for regulation as required under EU-FLEGT.41

Unchecked logging creates a stark landscape in Myanmar. Photo by jidanchaomian via Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Limited Data

Data and transparency on production and MTE financials have been limited.42 Illegal logging and exports are difficult to capture, and also lack data. However, improvements are being made. In 2019, the Myanmar Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative released forest production and revenue data for 2014-15 and 2015-16.43 This is significant, and includes regional production totals and an attempt to reconcile government and company data. However, this data differs greatly from external data, which the MEITI acknowledges is a cause for concern.44 For example, ITTO reported about 4.2 million cubic meters of logs produced in 2014, while MEITI reported roughly 1.2 million cubic meters for FY 2014-15.45, 46

New Directions

The United States and European Union had for many years banned imports of timber from Myanmar. Despite this, it was widely suspected that imports of Myanmar teak were continuing to make their way to the US and EU through third countries.47 However, with the general lifting of sanctions in 2014 and 2016 came new engagement.

In 2015, the EU began discussions with Myanmar to develop a Voluntary Partnership Agreement under the EU-FLEGT program. This program requires the development of a “Timber Legality Assurance System,” to guarantee the sustainability and legality of timber exported to the EU.48 The conclusion of a VPA is still some time away, but the process of mapping current timber flows is under way.49

Since 2011, Myanmar has also participated in REDD+, a framework under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change through which developing countries are paid for reductions in emissions associated with deforestation and degradation, and improvements in sustainable forest management. Baseline data, called the Forest Reference Emissions Levels, was submitted in 2018, along with a draft National Strategy for public comments and workshops. This draft is no longer unavailable online.

Finally, Myanmar has taken steps towards more participatory forest governance. The current National Forest Master Plan (2001-2031) sets a target of 919,000 hectares under Community Forestry.50 The latest data from 2019 show 248,711 hectares under Community Forestry and 4,707 recognized Community Forest User Groups.51 The Community Forest Unit within the Forest Department and the multi-stakeholder Community Forest National Working Group are working together closely to improve the legal framework for community forestry and support its implementation.

References

- 1. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2017. Forest Change in The Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS): An overview of negative and positive drivers. Accessed October, 2019.

- 2. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2014. Fifth National Report to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. Accessed October, 2019.

- 3. Wildlife Conservation Society, “Myanmar: Wild Places: Southern Forests.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 4. The World Bank. 2019. “Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis. Sustainability, Peace, And Prosperity: Forest Resources Sector Report.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 5. Ibid.

- 6. Ibid.

- 7. Ibid.

- 8. EU FLEGT Facility. 2011. “Baseline Study 4, Myanmar: Overview of Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. Promotion of Indigenous and Nature Together Myanmar. “Status of Shifting Cultivation and REDD+ in Myanmar.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 11. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2017. Forest Change in The Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS): An overview of negative and positive drivers. Accessed October, 2019.

- 12. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2014. “Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015 Country Report: Myanmar.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 13. Ibid.

- 14. Ibid.

- 15. Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation. 2018 “Myanmar Forest Reference Emissions Level (revised).” Accessed October, 2019.

- 16. Ibid.

- 17. Thomas Enters and Gabrielle Kissinger, UN-REDD/Myanmar Programme. 2017. “Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Myanmar.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 18. The World Bank. 2007. “At Loggerheads? Agricultural Expansion, Poverty Reduction, and Environment in the Tropical Forests.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 19. Thomas Enters and Gabrielle Kissinger, UN-REDD/Myanmar Programme. 2017. “Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Myanmar.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 20. Ibid.

- 21. Thomas Enters and Gabrielle Kissinger, UN-REDD/Myanmar Programme. 2017. “Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Myanmar.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 22. Fu-Jiang Liu, et al. 2015. “Assessment of the Three Factors Affecting Myanmar’s Forest Cover Change using Landsat and MODIS Vegetation Continuous Fields Data.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 23. Thomas Enters and Gabrielle Kissinger, UN-REDD/Myanmar Programme. 2017. “Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Myanmar.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 24. EU FLEGT Facility. 2011. “Baseline Study 4, Myanmar: Overview of Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 25. Thomas Enters and Gabrielle Kissinger, UN-REDD/Myanmar Programme. 2017. “Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Myanmar.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 26. Kevin Woods. 2013. “Timber Trade Flows and Actors in Myanmar: The Political Economy of Myanmar’s Timber Trade.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 27. EU FLEGT Facility. 2011. “Baseline Study 4, Myanmar: Overview of Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 28. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2014. “Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015 Country Report: Myanmar.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 29. Xinhuanet, 2018. “Myanmar to implement 10-year reforestation plan.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 30. Environmental Investigation Agency. 2019. “State of Corruption: The Top-level Conspiracy Behind the Global Trade in Myanmar’s Stolen Teak.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 31. Oliver Springate-Baginski, Thorsten Treue, and Kyaw Htun. 2016. “Legally and Illegally Logged Out: The Status of Myanmar’s Timber Sector and Opportunities for Reform.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 32. International Tropical Timber Organization. 2018. “Plans to restructuring MTE with private sector management.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 33. Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation. 2018 “Myanmar Forest Reference Emissions Level (revised).” Accessed October, 2019.

- 34. EU FLEGT Facility. 2011. “Baseline Study 4, Myanmar: Overview of Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 35. Ibid.

- 36. Sophie Song, IBTimes. 2014. “Myanmar Imposes Export Ban To Stop Its Timber From Foreign Exploitation, Goal Is To Establish Domestic Wood-Processing Industry.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 37. Htun Htun, Irawaddy. 2019. “Government Lifts Ban on Plantation Teak Exports.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 38. Thomas Enters and Gabrielle Kissinger, UN-REDD/Myanmar Programme. 2017. “Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Myanmar.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 39. Oxford Business Group. 2016. “Myanmar Report: Myanmar Balances Forestry Exports with Preservation.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 40. Kevin Woods. 2013. “Timber Trade Flows and Actors in Myanmar: The Political Economy of Myanmar’s Timber Trade.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 41. Ibid.

- 42. Oliver Springate-Baginski, Thorsten Treue, and Kyaw Htun. 2016. “Legally and Illegally Logged Out: The Status of Myanmar’s Timber Sector and Opportunities for Reform.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 43. Myanmar Extractive Industries Transparency Index. “Publications.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 44. Myanmar Extractive Industries Transparency Index. 2019. “Report For The Period April 2015 – March 2016—Forestry Sector.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 45. Myanmar Extractive Industries Transparency Index. 2019. “Report For The Period April 2014 – March 2015—Forestry Sector.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 46. Myanmar Extractive Industries Transparency Index. 2019. “Report For The Period April 2015 – March 2016—Forestry Sector.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 47. EU FLEGT Facility. 2011. “Baseline Study 4, Myanmar: Overview of Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 48. EU FLEGT Facility. “The EU Timber Regulation and VPAs.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 49. EU FLEGT Facility. “Myanmar: Activities.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 50. The World Bank. 2019. “Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis. Sustainability, Peace, And Prosperity: Forest Resources Sector Report.” Accessed October, 2019.

- 51. The World Bank. 2019. “Myanmar Country Environmental Analysis: Sustainability, Peace, and Prosperity: Forests, Fisheries, and Environmental Management—Assessing the Opportunities for Scaling Up Community Forestry and Community Forestry Enterprises in Myanmar.” Accessed October, 2019.